Measles causes more than an acute illness: it suppresses immune memory and increases the risk of complications for years.

The author Roald Dahl wrote a public letter describing his daughter’s measles infection in 1962, the year before vaccination became available.

Olivia, my eldest daughter, caught measles when she was seven years old. As the illness took its usual course I can remember reading to her often in bed and not feeling particularly alarmed about it. Then one morning, when she was well on the road to recovery, I was sitting on her bed showing her how to fashion little animals out of coloured pipe-cleaners, and when it came to her turn to make one herself, I noticed that her fingers and her mind were not working together and she couldn’t do anything.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

“I feel all sleepy,” she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.

The measles had turned into a terrible thing called measles encephalitis and there was nothing the doctors could do to save her. That was twenty-four years ago in 1962, but even now, if a child with measles happens to develop the same deadly reaction from measles as Olivia did, there would still be nothing the doctors could do to help her.

Dahl’s story shows how measles can strike suddenly and unpredictably. Itʼs also an important reminder that we need to understand not just its immediate dangers but also the lasting effects it can have.

Even today, measles-caused encephalitis (a dangerous inflammation of the brain) is difficult to treat. Although three-quarters of those who develop it survive the condition, out of those who survive, around one-third will sustain lifelong brain damage.1

Measles is often seen as a routine childhood illness — a fever, a rash, and recovery — but complications are common. Even when it doesn’t kill, measles can cause lasting damage. It weakens the immune system, making people vulnerable to other infections for months or years. That means children who seem to recover may still face serious health risks long after the illness is gone.

In some countries, measles has re-emerged in recent years, leading to outbreaks that many thought to be a thing of the past. At the same time, the case for vaccination has come under renewed scrutiny. If measles deaths are rare in high-income countries, why worry?

But evaluating the harm caused by measles isn’t just about the number of deaths. It’s also about what the disease does to the immune system and the chain of complications it can set off. Preventing measles matters — not only to stop the virus but to protect children from subsequent infections.

In this article, I explain how measles spreads and damages the body’s defenses, and why preventing it is still critical.

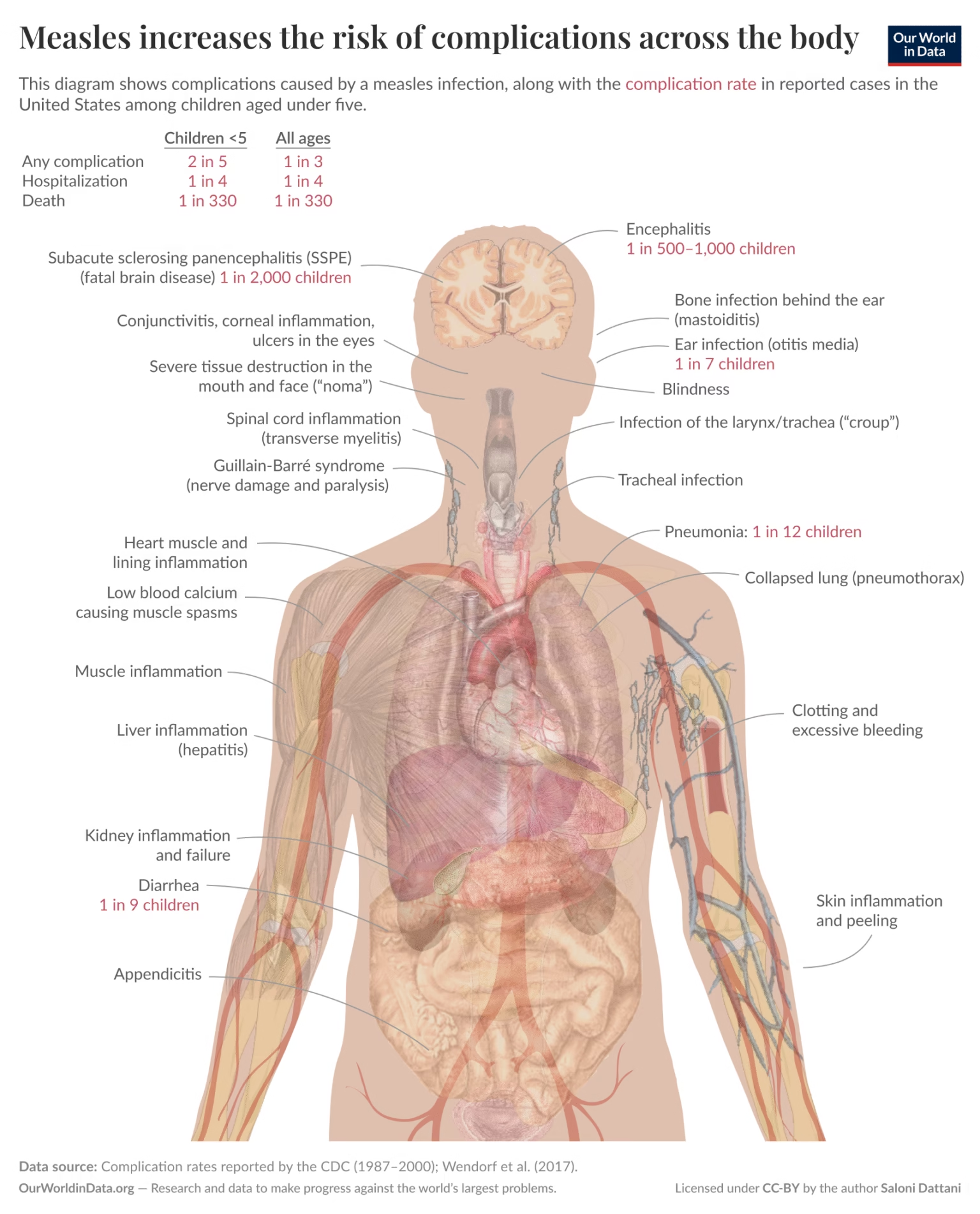

In the United States, deaths fell before vaccines, but measles remained dangerous

The chart below shows the number of measles cases and deaths in the United States since 1919. You can see that the number of deaths from measles began to fall several decades before vaccines were introduced in 1963.

The decline likely resulted from better treatment of secondary infections, improved sanitation and hygiene that limited their spread, and better childhood nutrition that lowered the risk of severe illness.2

However, we shouldn’t think this meant measles was no longer a public health issue. Although deaths had fallen, measles was still far from mild: before vaccines arrived, there were about 50,000 hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths each year in the United States alone.3

Large outbreaks also continued because measles remained extremely contagious until vaccination rates rose. The time series for cases in the chart shows that while there were often annual fluctuations, cases didn’t decline in a sustained way until the 1960s.

Because measles is airborne, clean water and sanitation weren’t enough to stop its spread. That’s because measles is also one of the most contagious diseases. On average, each person infected with measles would infect 12 to 18 other people in a population without immunity, which means it could spread very rapidly across the population.4

So, without vaccines, measles deaths couldn’t be eliminated, and we couldn’t stop cases either — leaving many people vulnerable to harmful and long-lasting complications of the disease.

In the next section, I’ll discuss what those measles cases meant and the complications children faced.

Measles spreads through the air and can cause complications across the body

The measles virus spreads through the air and can be inhaled into people’s lungs as they breathe. It infects immune cells in their airways, where it hitches a ride to their lymph nodes, which coordinate their immune responses.

There, it finds its main targets — memory T and B cells, which help the immune system recognize past infections. But, instead of fighting the virus, these cells become its transport and carry it deeper into the bloodstream; measles turns the body’s defense system against itself. Now, the virus can spread into the thymus, spleen, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, liver, and skin.5

However, visible signs of infection only appear after one or two weeks. Fever, cough, runny nose, and red, inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis) are common. These symptoms worsen over days, before tiny, blueish-white dots (known as “Koplik’s spots”) appear on the inside of the cheeks.1

Blood vessels in the skin swell and leak, resulting in characteristic red patches called the “measles rash”, which start on the face and neck. Over the next few days, the rash spreads from the chest to the back, arms, and legs. Individual spots merge into large, inflamed patches, fever spikes, and the body struggles to control the virus.1

By multiplying rapidly and spreading across the body, the virus can leave children vulnerable to many complications and additional infections for years.

As measles infects immune cells, it depletes important cells that provide the body with memory of past infections and help protect against them.

The loss of immune memory caused by measles — often called “immune amnesia” — leaves a gap for other infections to take hold.

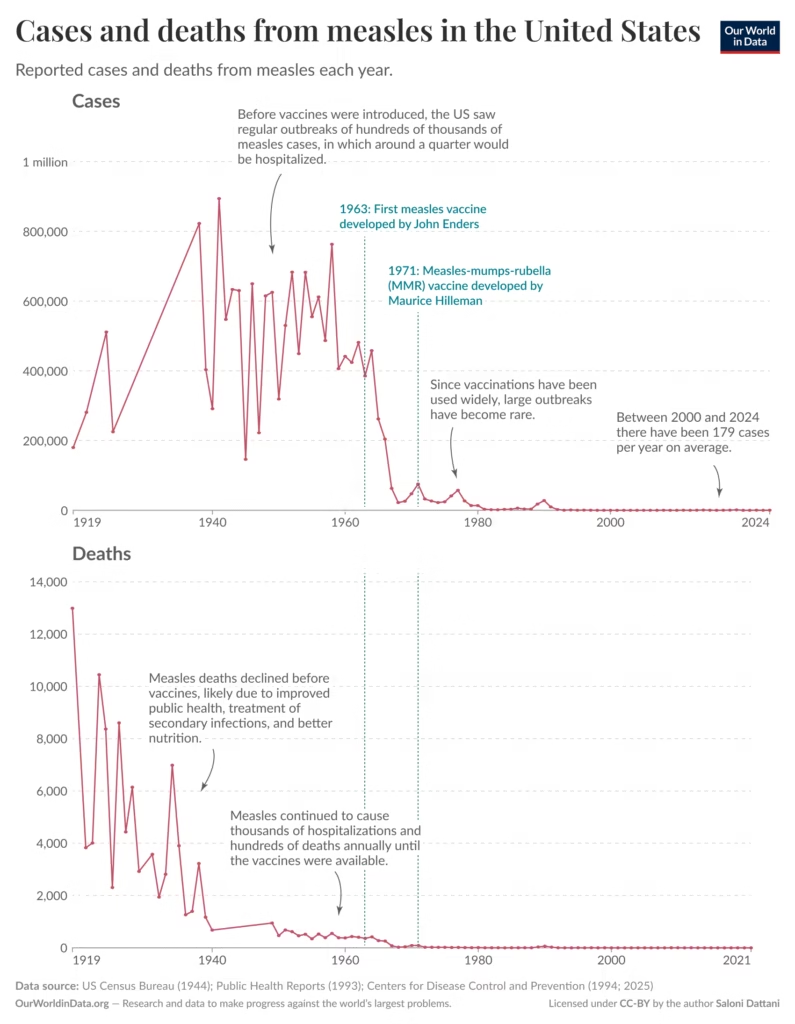

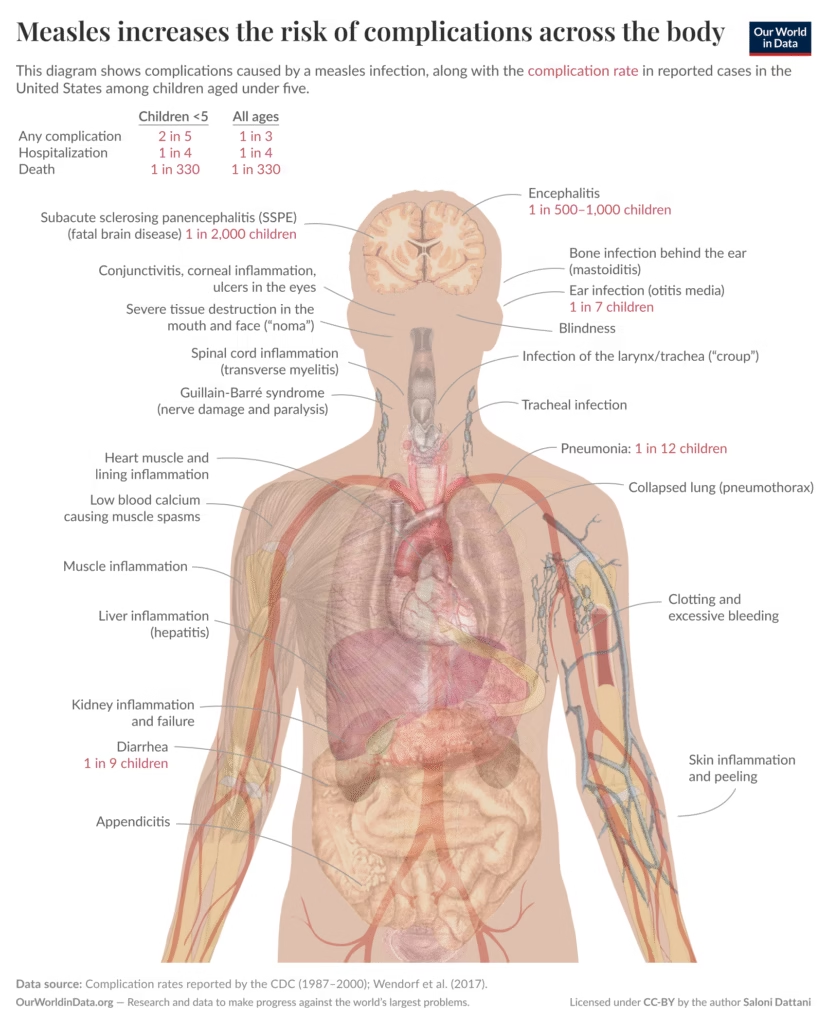

This can result in ear infections, pneumonia, diarrhea, dehydration, malnourishment, blindness, and brain swelling.5

In the diagram, I’ve illustrated the many ways that measles can lead to complications across the body.

Estimates from Perry and Halsey (2004); Wendorf et al. (2017)

Measles can also cause several rare complications. One is “noma”, a condition where mouth ulcers develop and eat away at soft tissue, resulting in facial disfigurement.

For one or two children in a thousand, the brain is affected as well: “post-infectious encephalomyelitis” can develop days after the rash fades and causes seizures, confusion, and paralysis. Of those who develop this condition, one in four die, and one in three survive with lifelong brain damage.1

The virus can also resurface as “subacute sclerosing panencephalitis” years later, which affects around 1 in 2,000 children.6 This is a condition where children initially appear irritable, screaming, and crying; their ability to think, make decisions, and control their body is gradually reduced until they’re in a vegetative state.7

Measles infections cause lasting immune damage

Even in a typical case of measles, children who survive the infection recover slowly.

The rash fades and peels away, but the immune amnesia means they remain vulnerable for the next few years to many other diseases that would normally be mild or harmless.5

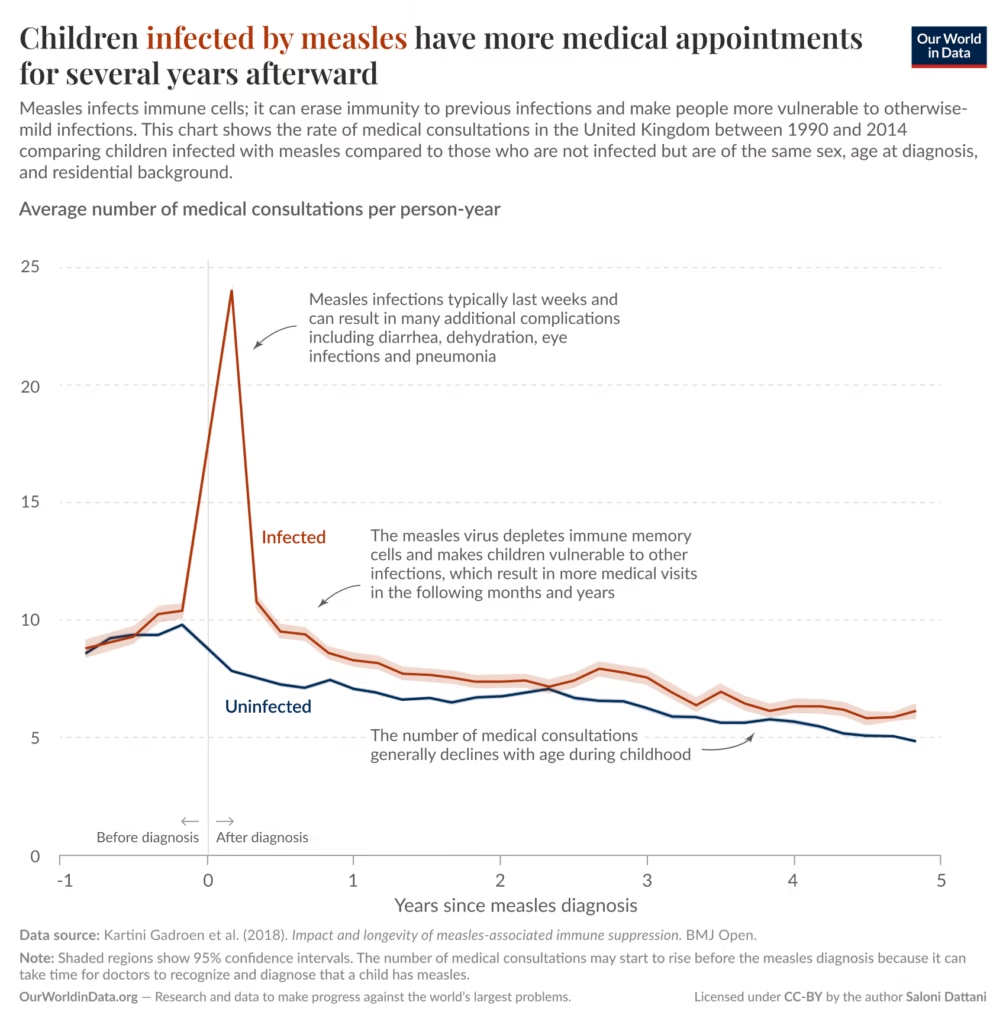

Evidence of this is shown in the chart below: children infected with measles use medical care more often for several years after their infection.

Complications from measles are most severe in infants and malnourished children, who have the highest fatality rates from the disease, as well as in pregnant women.9

In high-income countries today, many people have never seen a case of measles. But it was a feared and familiar part of childhood before widespread vaccination. The virus could sweep through communities, hospitalize a quarter of children, and leave some blind, with lasting breathing difficulties, permanent brain injury, or dead.

The suffering caused by measles was part of everyday life. Now, in places where vaccination rates have fallen, that past is starting to return.

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases, and it doesn’t just cause rashes. It infects and destroys important white blood cells, which are critical for the body’s defenses against infections.

By targeting memory T and B cells, measles weakens the immune system by erasing its memory of past infections. As a result, children remain vulnerable to other diseases for years.

The good news is that measles is preventable. With widespread vaccination, we can stop its spread, protect our immune systems, and prevent needless suffering.

When we prevent measles, we’re not just avoiding one illness. We’re also preserving the immune system’s knowledge of previous infections. That’s because vaccination doesn’t just stop measles; it also protects the body from the lasting damage the disease leaves behind.

Citation

Saloni Dattani (2025) – “Measles leaves children vulnerable to other diseases for years” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/measles-increases-disease-risk’ [Online Resource]